Short Introduction for the Association of Science In Schools.

THE GRAVITY OF LIFE by Andrew K Fletcher

Introduction: All life on earth developed with one thing in common; Earth!The constant forces are gravity, and the energy from the sun.

The most abundant resources are minerals and water.

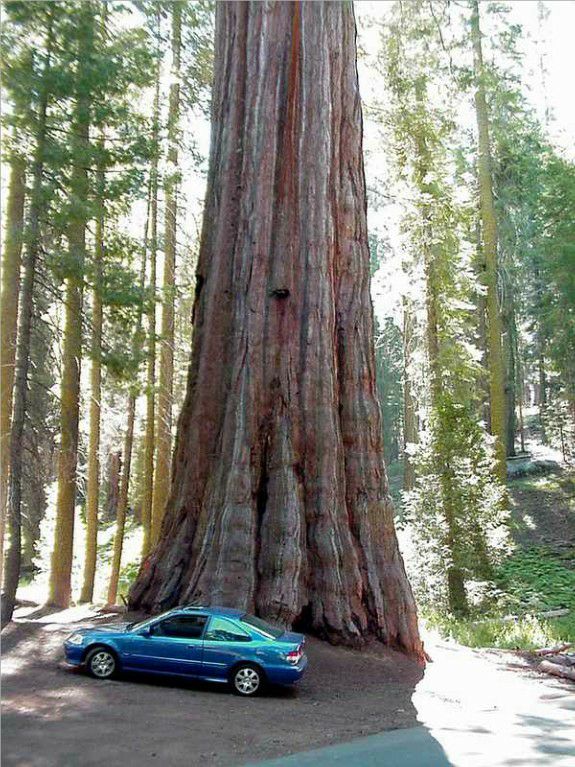

Plants and animals alike, all depend on the properties of water for transporting minerals and nutrients. Because life is based on water, in that everything alive started from a few drops, life must have evolved by finding the easiest and most direct pathway, after all liquids are very good at finding the most direct route possible. Yet, at first glance, everywhere one looks life appears to have chosen the least likely of paths, if it is trying to overcome the effects of gravity. Would trees, with species like the giant Californian redwoods (sequoia sempervirens) , towering over a hundred metres high have chosen a vertical direction? How then have plants and animals harnessed the constant pull of gravity in order to thrive and grow?

On a summer day a large oak tree may take up a hundred gallons of water or more, enriched with minerals and nutrients from the soil. At first glance it is doing so against the pull of gravity, producing flow rates, which cannot be explained or shown by working models based on osmosis, capillary action or root pressure. So how are trees doing it?

Explanation:

Over 95% of the waters drawn in at the roots of a tree evaporate into the surrounding air through the leaves by transpiration. The evaporated moisture contains no minerals. However, the water remaining inside the tree contains a variety of mineral salts dissolved from the soil, together with sugars produced by the tree. The transpired water results in a concentration of salts and sugars within the leaves. Concentrating a liquid, (sap), which contains substances that are heavier than water, must result in the production of a heavier solution than the pre-transpired liquid. Because of the resulting imbalance in density the heavier solution is drawn towards the base of the tree, due to the effect of gravity (maple syrup, latex and amber are evidence for this). Downward flowing sap occurs predominantly within the phloem vessels. When an excess of concentrated liquid is produced during favourable weather conditions, the downward flowing sap forms new tubes from the cambium, as it is forced down by gravity, in a continual cycle of growth.

In hard woods, sap flows from cell to cell through openings or perforations, in the membrane between abutting vessels.

In soft-woods, the sap flow controls movable valves, or pits - (thin areas), in the walls of conducting tracheids. Concentrated pulses of sap may eventually be found to be present in some xylem vessels, as gravity inevitably finds the most direct route, with the least resistance, to the ground.

But for every action there must always be a reaction, and the reaction in this case is that the downward flowing liquid behaves exactly like a plunger in a syringe. As it flows down it causes the entire contents of connected tubes filled with the less dense liquid to be drawn up.

Here we have a simple power source, which is driven purely by evaporation, posture and gravity.

The forces produced by this phenomenon are easy to demonstrate in simple tubular experiments. The main forces are produced at the head and tail of the falling solutions. The head produces a positive force, or pressure, and the tail produces a negative pressure. I believe that the positive force within the mineral laden sap is responsible for the formation of the tubular structures found in timber. The positive force prevents tubes from closing.

As more sap flows through the same pathways, some of the sap is used to strengthen the tubes which will eventually become strong enough to resist the negative pressures. The tree transports the dilute solution of water and minerals to the leaves using these tubes. Thereafter becoming what we call the xylem vessels.

As the concentrated liquid falls towards the ground, minerals are locked away as timber, while the mineral laden liquid arriving at the roots is inevitably re-diluted by the dilute solution drawn from the soil. The imbalance in the liquid is corrected as it becomes lighter or less dense than the downward flowing sap and begins its journey back to the leaves, where the process continues, providing the tree with a constant supply of water and nutrients.

In the autumn, when the leaves have fallen, the circulation is altered as a greater positive pressure is exerted towards the roots, because transpiration has ceased and therefore fluids flowing towards the top of the tree would be compromised. At this time of the year root growth would be most productive.

As fluid channels begin to offer resistance, the sap must find alternative routes. The new directions may be vertical or horizontal, but always in the path of least resistance. Eventually tubes become redundant and new tubes are formed. Fluids of different specific gravity have been observed to flow in both directions, simultaneously while in the same tube. In fact this ‘transpiring gravitational flow system’ is able to operate without tubes and has been attributed to causing the oceans to circulate (Atlantic conveyor system).

Early attempts at lifting water: The story goes that the reigning Grand Duke of Tuscany had ordered a well to be dug to supply the ducal palace with water. The workmen came upon water at a depth of 40 feet, and the next step was to pump it up. A vacuum lift pump was erected over the well, and a pipe let down to the water, but the water was found to rise to a height of 33 feet and no more, in spite of the most careful overhauling of the pump mechanism. It was at this stage that Galileo was consulted. While the famous philosopher was unable to offer a solution, he at least indicated the problem. Here above the 33 feet of water was seven feet of vacuum. The limit for raising water by suction in a tube appeared to be thirty-three feet.

Why should there be this limit when trees are observed to ignore it?

By introducing a loop of tubing, instead of a single tube, to simulate the internal structure of plants and trees, and suspending it by the centre, the problem of raising water above the 33 feet limit is solved. The reason a loop of tubing succeeds where a single tube fails is because the cohesive bond of water molecules is far stronger than the adhesive qualities of water observed in Galileo’s lift-pump problem. Using a loop of tubing enables water molecules to bond to each other in an unbroken chain. It helps to picture the unbroken loop of water as a cord instead of a liquid, supported by a pulley in the centre with tension applied to both ends.

The columns of water held in both sides of the tube exert a downward force due to the weight of the water contained in the tube. This force causes the water molecules in the tube to be stretched, causing the water to behave like an elastic band. In order to demonstrate this affect on water molecules I repeated the experiment shown in figure 1 without the added saline solution, the two open ends of the tube at ground level were removed from the demijohns, exposing them to the air.

Though the tube contained water, it did not flow from either side of the tube. In fact the opposite effect was observed; the water level in both sides of the tube immediately rose to a new level about half a metre from the ends of the tube. Even more surprising the water columns stayed there suspended by the cohesion between the water molecules.

In order to try to upset the balance I then blew up one side of the tube, causing the water level on that side to rise. I then released the pressure and the water returned to the same equal level. This observation offers an exciting explanation to the problem of explaining why water does not pour from the wound when a tree is felled.

However, the present laws of physics state that water cannot exist in its liquid form below 4.6 torr, yet the water remains in the tube. Only when the tube is lowered, or if a bubble appears at the top of the loop of tubing does the water flow out from the open ends.

THE BRIXHAM CLIFF EXPERIMENT

This experiment successfully demonstrated fluid transport to a height, which exceeds the current accepted limit of 10 metres and how this applies to the way that trees draw water to their leaves.

APPARATUS

48 metre single length of clear nylon tubing, 6.35 mm inside diameter x 9.5 mm outside diameter (type used to draw ales in the brewery trade), two clear glass demijohns, a large tray, 50 mils of concentrated salt solution with added red food dye, 50ml syringe minus the needle, sufficient degassed or previously boiled and cooled water to fill the tubing, the demijohns, and for adequate top ups. Adequate nylon cord to hoist the tubing and pulley to the desired height, a small pulley and adhesive cello-tape.

Method

The two bottles were filled to the brim with the water and placed in a suitable tray to catch any displaced water. The length of tubing was half filled with the water by siphoning. This was achieved by submerging one end of the tube in the water filled demijohn placed on a table. When the water reached the centre of the loop, the open end of the tube was capped with a thumb. The end of the tube in the demijohn was removed and the 50 mils of coloured salt water was introduced via the large syringe. The demijohn was then re-filled to the brim and the tube was re-submerged, making sure that no bubbles were introduced by adjusting the height of the unfilled side of the tube. By removing the thumb, the remaining length of tube was filled and again capped, making sure that no air was trapped inside the tube. At this point the demijohns were, refilled. The capped end of the tube was then inserted into the other water filled demijohn and both ends secured at an equal level, with cello-tape, again making sure that no air was allowed to enter the tube.

A length of the nylon cord equal to that of the length of tubing used was passed through the pulley, provided a safe ground level means to hoist the loop of tubing to the desired height. The pulley and the main nylon cord was hoisted to the desired height and secured at the top of the cliff on a separate length of cord. Adhesive cello-tape was wrapped heavily around the two sides of the loop of tubing 15cm from its centre to secure one knotted end of the main nylon cord, which ran through the pulley for the purpose of lifting the tube, taking care not to reduce the tubes diameter. The cello-tape was used to bind the cord to the tube.

Coloured insulation tape was used to secure both sides of the tube together providing an excellent ascent measurement when placed at one-metre intervals.

The Original Brixham Cliff Experiment on Youtube:

The centre of the tube was then gently hoisted, taking care to keep the ascent as smooth as possible. As the tube was raised the salt solution began to fall, due to the influence of gravity; this caused one of the demijohns to start overflowing indicating a positive pressure, while the second demijohn began to lose water at the same rate indicating a negative pressure. The emptying demijohn received frequent top ups, until the salt solution arrived at the overflowing demijohn and the flow stopped.

Conclusion

The fifty mils of salt solution caused the water in the tubes to circulate. The amount of water displaced and collected in the tray represents approximately the volume of water held in one side of the tube. Which meant that the fifty mils of salt solution had lifted water from one demijohn to the height of 24 metres and caused water many times its own weight and volume to rise. (I have used as little as 10 mils of coloured salt solution in the same experiment with a slower rate of decent but with similar displacements of water). Initially the experiments were tested at lower levels of elevation. 24 metres vertical lift was achieved when demonstrating the phenomenon before an audience of journalists and Forestry Commission scientists at the Overgang cliff, Brixham, July 1995. See Press Cutting

Bench demonstration (pictured above) Video of experiment on Youtube

For the purpose of demonstrating this phenomenon use a scaled down two metre high version of Fig 1. Substituting the demijohns for small narrow necked bottles. The type of tubing used to oxygenate aquariums is ideal for this purpose. A two-mil syringe minus needle, filled with coloured salt solution, connected to a T piece via a short length of tube, may be added close to the centre of the elevated tube to introduce salt solution intermittently while the tube is elevated, providing multiple demonstrations. Furthermore, the tube used in the salt free side of the experiment, (return side), may be of a larger bore size. Soft wall, silicon tubing shows visible signs of distortion when the saline solution is allowed to flow through it. The side containing the saline solution expands while the other side contracts, again indicating the presence of both positive and negative, pressures.

The experiments shown have been repeated using a variety of substitutes for salt solution, such as strong tea solution, fruit juices and milk etc. in order to relate directly to plants and animals. The flow rates achieved using different solutions, produced different rates of flow.

Umbrella Plant Experiment, (cyperus alternifolium)

In order to demonstrate that liquids of higher concentrations move through plants in relation to the constant pull of gravity. Take a freshly cut stem about 15cm long, with leaves intact, from an umbrella plant. Place the cutting upside down, in a glass container of water. After several weeks the umbrella plant starts to grow roots from what was the top of the plant and new stems are produced, as the shoots grow vertically in the normal way. The liquid processes involved within the plant for both root and leaf production, must have travelled from one end of the cut stem to the other. Indicating that gravity has an important influence.

When relating back to trees, the negative pressure, observed in the demijohn with the falling water level, provides us with a clear understanding of the mechanisms involved in drawing water through the roots from the soil. The positive pressures caused by the weight of the column of water held in the tree, plus the additional influence of gravity acting on the concentrated solutions, induced by the loss of moisture at the leaf, provides the roots with sufficient power to penetrate the earth.

Explanation for fluid exuding from a cut stem.

To demonstrate this effect, fill a vertically held open ended u tube with water, Fig 2A, and add a little coloured concentrated salt solution to one side, Fig 2B, the level of the salt solution will drop causing the opposite side to overflow. Imagine the loop of tubing is one of many tubes in the stem of a freshly cut plant or tree with roots in the soil. The overflowing water represents the xylem sap rising under the influence of the positive pressure, generated by gravity acting upon the concentrated sap in the phloem tube.

This is an important observation that gives a clear understanding of why plants and trees continue to grow upwards.

Little or no cross contamination takes place between liquids in the clean-water-side and the coloured saline side of the tube. Fig 2 C, I have left this experiment suspended for five days and it appears to remain stable. Circulation within an enclosed system, Fig 3, eliminates siphon as an explanation, demonstrating that flow occurs inside and would continue to do so if the tube was pressurised.

See video of experiments on Youtube

The thin columns of water in trees are known to snap, making a cracking sound through a stethoscope. Cavitation occurs immediately the bead of water separates. The formation of gas at the uppermost part of the raised loop of tubing, Fig 1, caused both columns of water to fall towards the ground and form a new level of 33 feet. The space above the water columns is a vacuum.

The circulation in trees continues, despite continuous cavitations, which means that they are able to refill or repair the vacuum. The internal part of a tree is a network of veins, or tubes, most of which run vertically. However some tubes run at an angle and some horizontally and provide links to other tubes, which interconnect at random levels. The internal tubular parts of the tree are themselves captivated inside a large tube, which is of course the bark or outer skin.

Water columns within the internal tubes of a tree, are continually stressed under a negative pressure, caused by downward flowing concentrated solutions within the trunk and branches. Cavitation occurs because the long thin columns of water are pulled apart. Immediately the cavitation forms, the internal pressures of that tube switch from a negative pressure to a positive pressure, forcing the more dilute solution in the opposing side of adjoined tubes upwards, Fig 2.B. & Fig 2 C. The downward force causes an increase in the head of water at the top of the tube. It is this increase in the head of water that gives a tree both momentum and direction to follow in its cyclical growth. Furthermore an increase in the positive pressure above the cavitation refills and repairs the vacuum, therefore enabling the tree to continue with water transport, and allowing gas bubbles to percolate upwards and out through the leaves.

This ability of the tree to switch from positive pressure to negative pressure and visa-versa gives us an understanding of the pressures observed in the roots of the tree. The roots being able to drive down through the earth under a positive pressure and expanding forces yet are still able to suck in water under a negative pressure.

Safety

· Students conducting any overhead experiments must observe the same Hard Hat safety regulations imposed on building workers.

· Experiments involving tube elevations higher than classroom levels should always be supervised. The safest area for this kind of experiment to take place is on a spiral staircase. Cliff top experiments are dangerous.

· A nylon line passed through a small pulley block, which has been secured at the desired height, enables the loop of tube to be elevated safely from ground level.

· Boiling water is dangerous and should not be handled or moved until it has cooled sufficiently enough to prevent scalding.

END Or Begining?

How does this fit with Human and animal circulation? Picture the drawing flat on a table. It does not work. Now picture it vertical or even at a slight head up angle and the whole drawing comes to life with a pich of salt added at the top to increase the density and introduce a driving force as it percolates down to the kidneys and in doing so causes the whole drawing to circulate.

2 comments:

How many scientists have read this and turned on ignorance?

Hi Andrew,

Maybe a lot. I'm an engineer very interested about your therapy. I read a lot of times but not making lot of progress in understanding!

You should really write a (pedagogic) book to explain the phenomena.

Thank you, I still try to understand better!

Post a Comment